For fans of colour, connection and art history, this fascinating exhibition is sure to please, finds Alex Fice

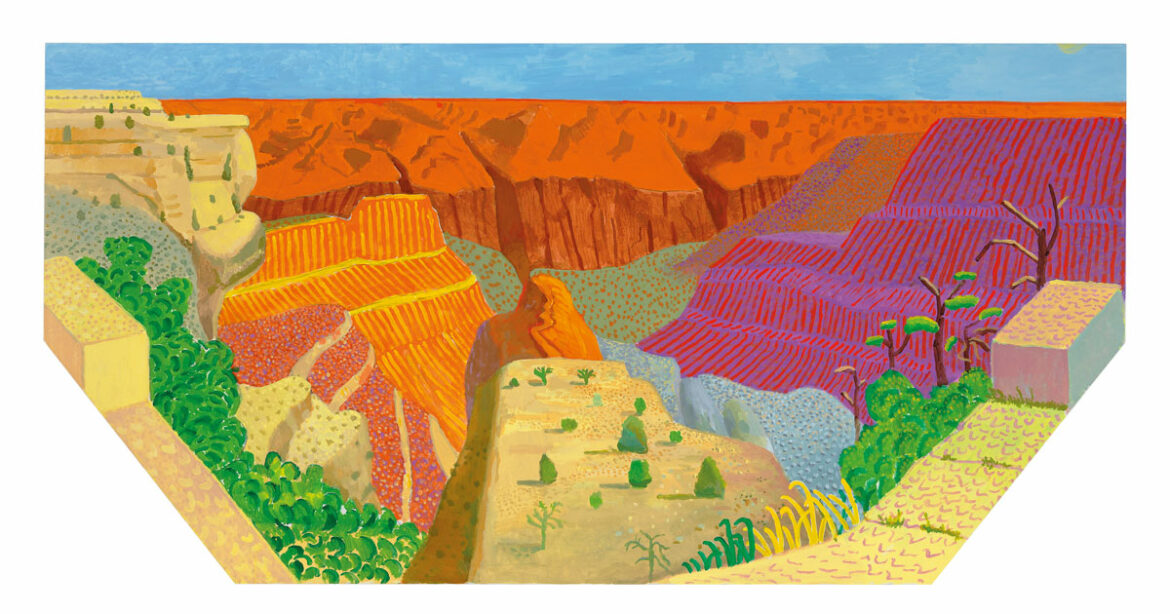

Image “Grand Canyon I” 2017 © David Hockney

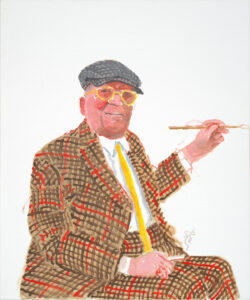

When we view an artwork, we see the world filtered through the eyes of the artist. Hockney’s Eye: The Art and Technology of Depiction – an exciting new exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum and Downing College’s Heong Gallery – offers us the opportunity to better understand the unique perspective of one of Britain’s most brilliant talents, David Hockney. Running until the end of August, the exhibition showcases the extraordinary range of his work – from paintings and drawings to iPad pieces and video – alongside optical devices and innovative 3D modelling. It also gives the chance to view never-before-seen artworks, including a highly anticipated self-portrait.

“Self Portrait, 22nd November 2021” © David Hockney

David Hockney has long been interested in the depiction of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional canvas. Throughout his astounding career as an artist, he has sought to radically question and subvert traditional representations of space and optical perspective. He has openly criticised the way that photography and linear ‘Renaissance perspective’ forces the viewer to absorb the scene all at once. Whereas, in reality, we take in our surroundings bit by bit, utilising our memory to construct the scene in its entirety. As Hockney would put it, ‘the eye is connected to the mind, therefore we see with memory’. This view has had a profound influence on how he represents the human experience of time and space in his art, be that in the form of photo-collage, digital drawing, multi-screen films or paintings.

Despite his rejection of certain formal conventions, Hockney is an artist with deep admiration for the master painters of the past, and their influence can be felt everywhere in his craft. Hockney’s Eye aims to explore art history from his unique viewpoint, by placing works in dialogue with some of the great creators on display at the Fitzwilliam Museum’s permanent exhibition. These careful juxtapositions allow us to notice similarities and differences between works, with careful attention to common themes, colours and subjects evident in the curation. “Comparisons are drawn between portraits by Hockney of his contemporaries, and by 18th-century artists Joshua Reynolds and William Hogarth, who were representing distinguished sitters and bluff merchants; drawings of flowers made with an iPad are displayed in one of the greatest galleries of flower paintings in the world. We also look at how Victorian artist Alfred Elmore’s way of painting shame resonates with Hockney’s image over a century later, and how Monet and Hockney captured a light-filled Normandy in spring,” says Jane Munro, keeper of paintings, drawings and prints and co-curator of Hockney’s Eye.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, Hockney’s approach to viewpoint comes to light, in the comparison of his reinterpretation of Fra Angelico’s Annunciation with two pieces by Domenico Veneziano – a contemporary of Angelico. In an innovative twist, computer vision has been used to show the actual spaces created by Veneziano in his paintings using linear perspective – revealing some surprises – and demonstrating how Hockney’s use of reverse perspective offers a more fluid approach to the depiction of space.

Another important aspect of Hockney’s perception of art history is his fascination with optical devices such as the camera obscura and camera lucida – as explored in his famous book, Secret Knowledge (2001). Hockney believes that many of the great draughtsmen of the past, such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, utilised these optical instruments to aid them in creating highly realistic drawings. This idea initially horrified art historians, but seemed entirely natural to Hockney. For him, using an optical device is no different from picking up a pencil – they are all tools in the same toolkit; it’s how they are used that matters.

There will be the chance to see several of these optical devices at the Fitzwilliam Museum, as well as drawings of Sir Ian McKellen, Damien Hirst and Martin Kemp – one of the exhibition’s curators – created using a camera lucida.

For Prerona Prasad, curator of the Heong Gallery – where the rest of the exhibition takes place – it is Hockney’s open and inquisitive approach to the use of technical instruments in art that makes him such an inspiring artist to observe. “For our community of students, we hope to demonstrate that disciplinary boundaries between humanities and sciences are porous; that the world and its challenges look very different depending on where you stand in relation to them. We hope they learn to look at the world through Hockney’s eye and discover the joy in truly seeing,” explains Prerona.

Hockney’s Eye offers the unique opportunity to experience the works of David Hockney in the context of the great artists that have preceded and inspired his work. The exhibition is open now until 29 August, with free admission for all.

Read our round-up of April art exhibitions here, and subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with all the latest.