This month, Dr Sue Bailey discovers a fruit worthy of the King’s table, with a 300-year link to Cambridge and the Fitzwilliam Museum

As you pass by the spiky, bright-golden pineapple ends on the black railings outside The Fitzwilliam Museum, you won’t find any bikes tethered to defile the historical site. But what is an enormous glowing yellow pineapple – lent by jelly makers Bompas & Parr – doing beside the somewhat affronted stone lions flanking the grand entrance to The Fitzwilliam Museum?

This symbolic fruit of welcome heralds a stunning exhibition that focuses on food in all its forms and is a feast for the senses, which is running from the end of November until mid-April. The ambitious interdisciplinary event not only includes hidden and newly conserved treasures, but also focuses on the physicality of food.

Feast Fast pineapple installation

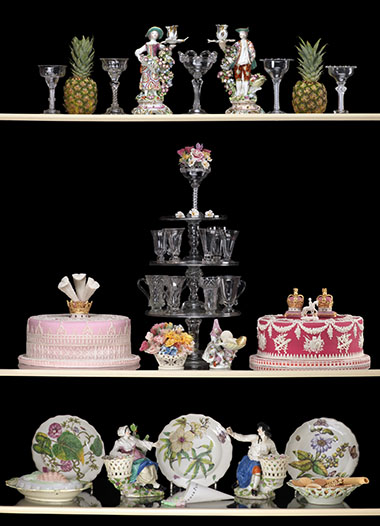

The creative elements linking the objects and art are the spectacular historical reconstructions, with food at the centre, produced by renowned food historian Ivan Day. Ivan is a scholar, broadcaster and writer, producing historic food recreations globally, as well as being a gifted professional cook and confectioner. For the exhibition, he has created a European feasting table replete with swan and peacock pies, plus a Georgian confectioner’s workshop with a pineapple ice cream mould among the display.

In addition, there is a Jacobean banquet featuring a beautiful sugar paste, tabletop version of the banqueting house at Melford Hall, including many disguised sugar foods, such as eggs and bacon, which draw in the senses to challenge the visitor to work out what is real and what is edible.

Dr Victoria Avery, keeper of applied arts at The Fitzwilliam, says: “One of the aims is to reanimate the objects and art work in the collection, and take people on a journey as to how these were actually used – for example, in Jacobean or Elizabethan times. Ivan has worked creatively, but accurately to interpret these, and the displays are visually stunning”.

Cultivation and consumption, together with the political, economic and cultural aspects of food, are linked to displays of preparation, equipment, early English cookery books, china, silverware and artistic inspiration.

The exhibition also aims to challenge the visitor to consider the religious and cultural ideologies around feasting and fasting, and how people make food choices, including examining early health and vegetarian movements. Dr Melissa Calaresu, historian at Gonville & Caius College and co-curator, tells me: “By the early 18th century, people were looking at vegetables in a different way. It wasn’t about putting lots of sauces, salt, sugar or spices on – it was letting the taste of the vegetable come through.”

Pineapples became so popular that growing them was a craze

But what of the pineapple? How can a fruit show power and status – and what have pineapples got to do with Cambridge? Christopher Columbus first encountered the pineapple in Guadeloupe at the end of the 15th century, finding it to be incredibly tasty and full of health benefits. Botanist John Parkinson described its taste “as if rosewater, wine and sugar were mixed together”. Although young pineapple plants were shipped from the West Indies to be matured in England, it was not until the early 18th century that, thanks to Dutch expertise, the first pineapples were grown from scratch on English soil.

The Cambridge and Fitzwilliam connection stems from the Dutch-born politician and merchant Sir Matthew Decker, the maternal grandfather of Richard, Viscount Fitzwilliam, founder of The Fitzwilliam Museum. Sir Matthew was so pleased with his Dutch gardener’s triumph in growing a tropical fruit in English soil in 1715 that, five years later, he commissioned a portrait of his fully grown pineapple flourishing in an English landscape. This is owned by the Fitz and marks the celebration of three hundred years of pineapple growing in England.

For his services to the crown, Decker was knighted and, that same year, invited King George I to dine and taste his pineapple. Pineapples became so popular that growing them was a craze for the rich, and was a fashionable test of good gardening by the end of the 18th century.

Recreation of an English confectioner’s shop window

Cambridge’s first professor of botany, Richard Bradley, was a good friend of Decker and published both botanical and cooking texts. These included the first recipes in English for “a Tart of the Ananas, or Pine-Apple from Barbados” and “Marmalade of Pine-Apples, or Ananas”. He also estimated it would cost £80 to grow a pineapple from planting to harvesting – equivalent to over £9,000 today – a symbol of wealth indeed.

Those who could not afford to grow their own could rent one for dinner parties, but they cost a guinea each, two if eaten. At Wimpole Hall, there is a pinery-vinery and the remains of pineapple pits where, in the 19th century, 250 pineapples were being cropped each year for the table.

To celebrate this glorious fruit, Ivan Day has used his own 18th-century pineapple mould to recreate the ice cream picture in the book produced to coincide with the exhibition. “A lot of academic writing on food ignores the food – but you have got to get your hands dirty and understand the food by actually making it,” he says.

Ivan emphasises that his aim includes how to bring the objects to life. “Confectioners carved their own moulds. These people were highly creative, highly skilled – the kitchen staff were innovative, helped by skilled artisans who made the kit. What has driven me is to really understand what it was like.”

The exhibition is also aiming for engagement and involvement with a community-produced film, multisensory experiences and a creative public response zone (painted yellow) at the end of the exhibition. Visitors can include their memories of feasting and fasting and reflect that ‘eating right’ in early modern Europe was as complex as making food choices now, and that our contemporary concerns about our relationship with food are nothing new.

So, come and hunt the Cambridge pineapple – and celebrate food and artistry in all its dimensions.

Feast & Fast runs at The Fitzwilliam Museum from 26 November to 26 April