Ruthie Collins finds out more about a local exhibition featuring work by revered artist Barbara Hepworth

A series of stunning abstract sculptures by Barbara Hepworth – one of the greatest British sculptors in art history – can be seen at Divided Circle at the Heong Gallery, Downing College, this month until Sunday, 2 February.

A prolific artist, Hepworth created more than 600 sculptures during her life, which can now be found all over the world. Cambridge is certainly no stranger to her work, with pieces on display at the Jim Ede House at Kettle’s Yard, in the garden of Churchill College, and at the New Hall Art Collection. But this is the first time that so many of her works have been exhibited together in one place in the city.

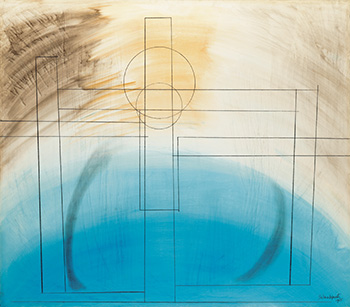

A selection of pieces made in the last 20 years of her life, this display demonstrates her work today has the same appeal and freshness as when she first earned recognition as a standout British sculptor within the Modernist movement.

The name of the show is inspired by keynote piece, Two Forms (Divided Circle), made in 1969, an extraordinary time for Hepworth. “I at last had space and money and time to work on a much bigger scale,” she said of this period. “I had felt inhibited for a very long time over the scale on which I could work… It’s so natural to work large – it fits one’s body.”

You can see the bronze sculpture on the grass outside the gallery, on loan from the Hepworth estate.

You can see the bronze sculpture on the grass outside the gallery, on loan from the Hepworth estate.

“She’s playing with our expectations, the shape is a circle from a distance, but the closer you get, you realise they are two forms, they have a force holding them together. I find it fascinating that she called it two forms first,” explains curator, Dr Rachel Rose Smith. “She’s trying to say that it’s both, that’s ok – people will see things differently. People and forms can be complex, that’s enriching.”

Many associate Barbara Hepworth with St Ives in Cornwall, but it was a remarkable meeting of artists here in East Anglia – not just with each other but with the natural landscape – that would change the course of British modern sculpture forever. Happisburgh, known to many Cambridge residents for its iconic striped lighthouse, is still full of the same distinctive ‘witch stones’ – pebbles with holes caused by natural water erosion – that fascinated Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore when they stayed there with friends in 1931.

There are not many artists who are that avant-garde, but also incredibly accessible

This interplay between form and absence still shines throughout Hepworth’s work. The piercing of form with holes became a signature for Hepworth, and she and Moore packed up four crates of the iron stone pebbles for carving after their holiday. This was also the spot where she fell in love with Ben Nicholson, forming one of British art’s great powerhouse couples.

Years later, the ‘pierced form’ remains a sign, of sorts, for modern art, marking a shift for sculpture itself, to invite interaction. “The carving and piercing of such a form seems to open up an infinite variety of continuous curves in the third dimension,” Hepworth wrote in 1946. “Here is sufficient field for exploration to last a lifetime.”

She was right. Many of the features that defined her work – curves and polish, a sense of connection to the landscape and material, the enriching relationship between space and absence – were developed throughout her life.

“Her later works were really sensual, bringing out our desire to touch things, love things. Emotional desire may come from motherhood, or infancy, like bringing up twigs, taking them home. It’s part of this desire to remind people of good things. People come away feeling like they’ve had a beautiful experience,” says Dr Smith. As Jeanette Winterson described, for Hepworth, “holes were not gaps, but connections”. Inspired, perhaps by the physicality of motherhood.

“Small Hieroglyph is a perfect opener. It relates to the human body and says so much about how clever she is, using forms that refer back to our own bodies,” says Dr Smith of the bronze piece, made in 1959.

In today’s modern world, marked by political crises and an escalation, perhaps, of the same sense of destruction that influenced Barbara Hepworth, this connectivity of art takes on a revitalised role. In 1947, Hepworth – fascinated by processes that heal – was invited to observe surgeons at work in a hospital. It’s no surprise that many of the resulting works feel like monuments to a harmonising beauty that unites and uplifts, from the flower-like effervescence of Forms In Movement (Galliard), to the bold, brilliant Miniature Divided Circle.

In today’s modern world, marked by political crises and an escalation, perhaps, of the same sense of destruction that influenced Barbara Hepworth, this connectivity of art takes on a revitalised role. In 1947, Hepworth – fascinated by processes that heal – was invited to observe surgeons at work in a hospital. It’s no surprise that many of the resulting works feel like monuments to a harmonising beauty that unites and uplifts, from the flower-like effervescence of Forms In Movement (Galliard), to the bold, brilliant Miniature Divided Circle.

“I was struck by how frequently she mentioned politics of the day, how society was becoming more destructive. She was willing to say this, her job was to say this when she could, but produce something that was very positive,” says Dr Smith. “The works are monolithic shapes, that could look like standing stones.

“There are not many artists who are that avant-garde, but also incredibly accessible. She would have wanted people to go with their own feelings.”

As a woman working in what was considered by many to be a man’s world, Hepworth was initially ambivalent towards being labelled a ‘woman artist’. “But from the 1960s, her gender becomes more positive. She writes a lot about the feminine in her work, she does interviews,” explains Dr Smith.

With so many stunning works in one show, it’s hard to leave without feeling optimistic. “There’s a sense of going back to earlier forms, a sense of completeness, of doing something more,” explains Dr Smith. “It’s like a pierced stone, but taken one step further.”

Divided Circle runs until 2 February at the Heong Gallery, Downing College.