As the Fitzwilliam Museum welcomes an exhibition inspired by Virginia Woolf, Ruthie Collins looks at the relevance of her pioneering ideas today, exploring her life, work and links to Cambridge

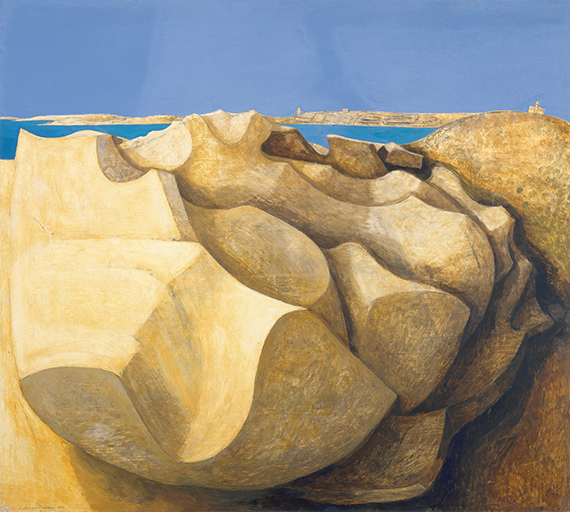

alking into Virginia Woolf: An exhibition inspired by her writings, currently on show at The Fitzwilliam Museum, vibrant lines and colour hit you, painted directly onto the walls by French artist, France-Lise McGurn. She was commissioned especially for this major touring exhibition, which has been to two other places that Woolf had strong links to – St Ives (at the Tate) and Chichester (at Pallant House Gallery). The result – light, fresh and full of strong feminine energy – continues throughout the show, which is structured into themes that feel glaringly relevant to women today.

“I thought it would be interesting to have an exhibition that was predominantly women, but would draw on the literary heritage of St Ives in Cornwall, where many writers visited, including Virginia Woolf,” explains Laura Smith, curator of the exhibition.

Woolf first delivered her lectures extolling the links between creativity, independence and women having a ‘room of one’s own’, at Girton and Newnham in Cambridge, 1929, which became the basis for her pioneering text of the same name. She had strong links to Cambridge; her father and brothers studied at Trinity Hall and she knew many Cambridge academics, from novelist E. M. Forster to pioneering economist John Maynard Keynes. The original manuscript of A Room of One’s Own is on display and has been digitised as part of the exhibition.

A radical, Woolf had strong links to the Suffragette movement, which you can see in the display of many original suffragette pamphlets and paraphernalia of the time – showing hatpins, fashion and style as a form of protest.

“Very little is known about women,” wrote Woolf in 1929. “The history of England is the history of the male line, not the female. Of our fathers we know always some fact, some distinction. They were soldiers or they were sailors; they filled that office or they made that law. But of our mothers, our grandmothers, our great-grandmothers, what remains?”

It was losing her mother as a young girl that led to the breakdowns that haunted Woolf for the rest of her life and for which she was treated with ‘containment’ – strict solitary confinement, void of all creative expression, fed on a fatty, milky diet. This jarring sense of loss of the mother – and Woolf’s yearning to restore the status of women through her feminism – permeates the show. “It’s sad many of the women exhibited are not well recognised throughout art history,” comments Laura Smith.

This strong sense of a matriarchal lineage of ideas touches on what Smith describes as a ‘constellation’ of connections between creative women, artists and intellectuals, rarely explored on such an ambitious scale. “I wanted to demonstrate that art is not a single lineage. It’s plural. There were lots of women artists and artists of all races and heritage, exploring themes that are not what we would naturally recognise as art,” she explains.

“Women in art were generally seen through a man’s eyes. This was about women seeing women,” comments Penny Slinger, on her work Perspective, from the series An Exorcism (1970-77), also on show. Fans of Judy Chicago’s infamous feminist installation, The Dinner Party, will love Vanessa Bell’s ‘The Famous Women’ dinner service, a 50-piece ceramic dish set featuring portraits of famous women from history. A private commission, barely exhibited until this year, the series is hand-painted on white Wedgwood.

“She was strict about who she allowed to paint her; the only paintings that exist by a woman of her were by her sister, Vanessa Bell. The portrait of Woolf included in the exhibition shows her and her sister at the height of her success,” Laura Smith says. This bond between Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf is one that many modern-day women will recognise as intellectually and artistically empowering, as well as sisterly. Bell designed dust jackets for Woolf’s books, Woolf reviewed her sister’s exhibitions. She found a strong sense of self in her, too. “I always feel like I am writing more for you, than for anybody,” Virginia once wrote to ‘Nessa’, as she called her sister. The female gaze, as encouraged through Woolf, can be transformative.

Woolf once commented that as creative women we ‘think back through our mothers’. “She’s talking about a lineage of women; this is an example of what that looks like,” explains Laura Smith. A creative sisterhood that has long been inspiring women across generations – often hidden or lost within art history.

Featuring works by a range of female artists including Vanessa Bell and other greats such as Barbara Hepworth and Romaine Brooks, as well as female surrealist artists often missed, such as Ithell Colquhoun and many living, contemporary female artists, this exhibition is a testimony to the legacy Woolf left to women today. Pioneering, radical – still needed.

Virginia Woolf: An exhibition inspired by her writings runs at The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, until 9 December.

Read Ruthie Collins’ regular monthly arts blog, The Art Insider, here