Cambridge seems like a city in many ways unchanged by the centuries. Walk down its cobbled streets, past churches and ancient college spires – a bicycle wobbling by – and it’s easy to imagine 100 years slipping away. Still, in 1914, the outbreak of the First World War impacted on life in Cambridge as it did the rest of the country; its students called up to fight and women left to work and nurse as Cambridge was transformed from quiet university town to military camp.

Outbreak of war

When war broke out in August 1914, Cambridge was a town (it wouldn’t gain city status until 1951) of horse-drawn trams and gas lamps with a population of around 40,000. The university was on its ‘Long Vacation’, and when students did return many of them jumped straight into military training.

“The suddenness of events in the first four days of August was staggering, and Cambridge was very quickly in the middle of military preparations,” writes S.C Roberts in The Cambridge Book of the Silver Jubilee. Soon caps and gowns had been replaced by khaki, and Pembroke College became the first officers’ school in the country. The atmosphere was one of excitement, recalls Arthur Sanctuary (A History of the University of Cambridge, Christopher N.L. Brooke), who had just completed a degree in theology at Caius. “We had a party to celebrate, which shows you how little we knew what it was going to be like.”

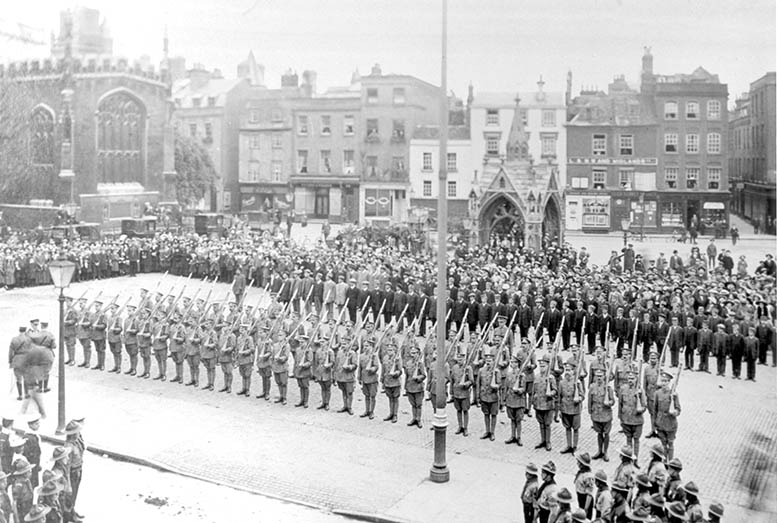

The Sixth Division were quartered in town and tents were pitched on Midsummer and Coldham’s Common, while on Stourbridge Common, “wandering crowds stood for hours gazing at horses, men, and the latest pattern of field guns” (The Cambridge Chronicle, 1918). Later, in the winter of 1916, soldiers were seen on Parker’s Piece throwing snowballs as hand grenade practice.

October 1914 also saw an influx of Belgian refugees, who were given residence in the city. The Cambridge Daily News, who reported the arrest of two spies on Midsummer Common in August 1914, printed their grim prediction of what might occur should the allies lose the war: “The University Library, Senate House and King’s College Chapel would be fired, shellfire would rake the range of colleges along the Backs, and the University labs would be razed to the ground. The mayor and vice chancellor, ministers of religion and editors of newspapers would be lined up and shot, male inhabitants herded into compounds, and women and children driven out.”

The First Eastern General Hospital

Still Cambridge rallied. In the summer of 1914 the First Eastern General Hospital was established within Trinity College. Mild weather meant beds could be made up around the cloisters before the hospital moved to its permanent spot, the old Kings and Clare playing field, where the University Library now stands. The hospital was built for 500 patients but expanded to hold over 1,000 by the end of the war. Patients were brought from the battlefields of France to Cambridge by train then transferred to the hospital by ambulance.

Ruth Dingley was an unqualified medical student at Newnham at the time who answered the call for nurses. In a recorded interview for IWM Duxford in 1988, she described her experience working at the First Eastern General Hospital in 1914:

“I don’t think I’d ever been in a hospital in my life. I was rather frightened of blood and abnormalities. I hadn’t done medical practice of any sort: I watched for about a week, in intervals of going outside to faint. By the end of the week I had stopped fainting. Then it was handed over to me to give the anaesthetics.” She continues: “There were two women in Newnham doing medicine and I got to know them. We went round doing these little concert parties for the soldiers. It was such a personal thing, the First World War, for all of my generation. I remember the first brother to be killed – it was a girl in my form. My brother was in France: he joined up on 20 August, was in France by September, utterly untrained. It was the flower of the younger generation that joined up.”

Ruth also warmly recalls Cambridge war poet Rupert Brooke, who died in 1915: “I remember a girl in my form coming in one day saying she’d met this wonderful new poet. We were crazy about him [Brooke], but Wilfred Owen we didn’t know.”

Listen to the full interview with First World War nurse Ruth Dingley here.

Women at war

Throughout the war, Cambridge emptied of young men save for conscientious objectors, foreigners and “men with bad hearts or feet”, remarked Girton student Edith Shuttleworth (Girtonians and the World Wars). Edith, like Ruth, was one of a handful of pioneering female ‘undergraduettes’ at the university, not yet granted full degrees and viewed with suspicion by male lecturers and students. “In those days women attended the university lectures on sufferance… we were completely ignored.” (Lily Baron, Girtonians and the World Wars).

For these women, college life went on largely as it had done; indeed lecture theatres were emptier and more jobs had by default opened up to them due to the lack of men. S.C Roberts recalls in The Cambridge Book of the Silver Jubilee: “Cambridge people became accustomed to seeing women do unfamiliar work: in December 1915, for instance, the first ‘postwoman’ set off on her rounds.”

At Girton, complaints were largely regarding the cold and lack of food, due to rationing and fuel shortages. “Never,” wrote A. M Dunlop, somewhat flippantly, “was the war brought home to us so truly as when we beheld a naked doughnut” (Girtonians and the World Wars). They knitted for the soldiers, grew vegetables and kept pigs, but in their gothic, castle-like college out of town, Girtonians remained somewhat removed from the outside world, the bubble puncturing dramatically on the occasion of bad news of sweethearts or brothers killed in action.

By 1918 the mood had darkened, as the Girton Review Lent Term 1918 recorded: “It seems impossible at the present time to enter heart and soul into any amusement. There is always a lurking feeling of uneasiness… that never allows us quite to forget the happenings of world-wide importance that are taking place not so far away.”

Threat from the air

Though Cambridge was too far for the guns of France to be heard, zeppelins were a very real threat. A blackout was introduced in January 1915 from 5pm- 7.30am (Philomena Guilebaud, From Bats to Beds to Books). Showing a single crack of light from your window could earn a householder a knock on the door from the special constable (The Cambridge Book of the Silver Jubilee).

In a letter, Girton student Constance Ryley recorded a ‘zep scare’ in 1917. Some girls, she says, climbed to the top of the tower after lights out and reported hearing bombs. The zeppelins had come for Newmarket, she reports, but were brought down on their way back to France. In From Bats to Beds To Books, nurses recalled seeing a zeppelin overhead in 1915. There was concern that the regimented hospital roofs would look like a factory from the air and be targeted. In the end no bombs were dropped on Cambridge – though one did fall in Bury St Edmunds, bringing the Germans a little too close for comfort.

Armistice

By the time the armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, according to The Cambridge Book of the Silver Jubilee, “It took an effort of imagination to realise any difference between term and vacation,” so empty had the university town become. Cambridge had given itself over to the war effort, suffered food shortages, the closure of businesses and the loss of a generation of men: the Roll of Honour at Cambridge Guildhall names 1,414 local men who fell in battle 1914-19.

Though there was rejoicing, the bells of Great St Mary’s ringing out across the city, the Cambridge Daily News reported the ransacking of a pacifist’s shop. The housing shortage due to an influx of returning troops triggered developments in Cavendish, Hills and Hinton Avenues, and in 1921 a vote was cast on whether or not women should be granted full membership to the university. Though women were eligible to vote from 1918, it was rejected – but that’s another story.

With thanks to: